In the contemporary digital age, knowledge is no longer simply a shared public good – it has become a commodified asset, repackaged, monetised, and relentlessly circulated by a new class of cultural actors: influencers.

Once confined to the fringes of media, these figures now dominate our feeds, shaping public discourse and occupying positions once held by intellectuals, journalists, or community leaders. The knowledge economy, in its current iteration, privileges visibility, virality, and charisma over substance, nuance, or critical inquiry. What we are witnessing is not the expansion of knowledge, but its substitution with influence – a shift with significant cultural and economic consequences.

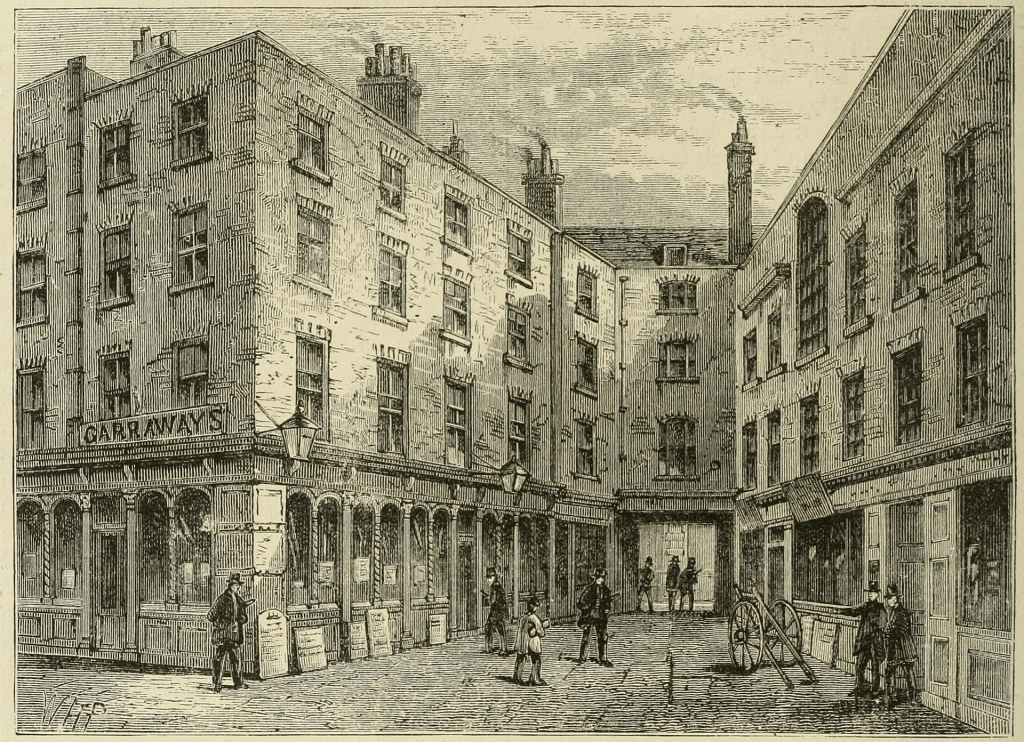

The roots of this transformation lie in the historical development of the public sphere. In Enlightenment Europe, particularly in the eighteenth century, coffeehouses and salons emerged as central spaces for debate, dissent, and the exchange of ideas across class lines. As described by Jürgen Habermas, these were not merely social venues but vital forums where private individuals came together to engage in rational-critical debate about public matters. These environments cultivated democratic participation and informed citizenship. They were foundational not only to liberal democracy but to the early mechanisms of capitalism itself; notably, the stock market originated in precisely these types of communal spaces, where trust, speculation, and shared discourse shaped economic life.

Garraway’s Coffeehouse in Exchange Alley, London

Contrast this with the fragmented digital landscape of the present. Today’s public sphere is governed not by rational discourse but by platform algorithms that prioritise engagement and emotional intensity over thoughtful exchange. Digital spaces that once promised democratic participation have devolved into arenas of performance, where content creators package themselves as brands and public dialogue is reduced to a monetised feedback loop. In this context, the influencer becomes the most visible node of the so-called knowledge economy, not because of their expertise, but because of their capacity to produce compelling, consumable narratives that convert attention into revenue.

This transformation of knowledge into content has profound implications. The language of “insight” and “value” is frequently invoked by influencers to signal depth or authenticity, yet these claims often obscure the underlying commercial motive. The problem is not that influencers profit from their work – profit, in itself, is not inherently corrupting – but that the structure of digital influence collapses the distinction between information and advertising, between discourse and product. As a result, critical thinking is increasingly displaced by a culture of consumption masquerading as self-improvement.

A central feature of this ecosystem is the perpetual cycle of personal optimisation. Under the guise of wellness, entrepreneurship, or “mindset” culture, individuals are encouraged to view themselves as projects requiring constant improvement. This ideology is reinforced through content that blurs the line between empowerment and coercion. Social media is saturated with advice on how to eat, think, exercise, journal, manifest, or monetise one’s time more effectively. This is not simply the diffusion of lifestyle tips; it is the internalisation of neoliberal economic logic, where even rest must be productive, and identity itself becomes a site of labour.

The influencer economy thrives on making people feel inadequate. It operates by perpetuating a sense of insufficiency – never productive enough, never healthy enough, never spiritually aligned enough. The solution is always the same: purchase access. Buy the course. Subscribe to the supplement. Align with the brand. And crucially, believe that you are doing it for yourself. This rhetoric of self-empowerment obscures the fundamental power imbalance at play. The influencer profits from your attention, your insecurity, and your aspiration, while maintaining the illusion that they are simply offering guidance or sharing what has “worked for them.”

“Wellness Aesthetic” on Pinterest

Even figures who claim to offer serious intellectual or business insight are embedded in this dynamic. Stephen Bartlett’s podcast, Diary of a CEO, presents itself as a platform for deep conversation about entrepreneurship and self-mastery. Yet the structure of the show – its format, guests, and sponsorships – ultimately serves to reinforce Bartlett’s own personal brand. The podcast becomes a vehicle not for critical thought, but for narrative control. It is a case study in the commodification of knowledge: ideas are presented not for debate, but for consumption.

This is the defining tension of the knowledge economy: knowledge is no longer valued for its capacity to inform or liberate, but for its ability to convert into profit. In such a system, truth becomes secondary to narrative, and insight becomes indistinguishable from influence. We must ask: who is producing this knowledge, and for what purpose? Who is fact-checking the narratives we consume? And what are the consequences when the most visible voices are those best positioned to monetise our attention?

Ultimately, the collapse of the public sphere into a marketplace of personalities has profound implications for civic life. It erodes the possibility of genuine democratic deliberation and replaces it with a form of digital feudalism, in which followers pledge allegiance not to ideas but to content creators. If knowledge is to retain any emancipatory potential, it must be reclaimed from this cycle of commodification. That means cultivating spaces – online or offline – where thought is not immediately monetised, where dialogue is not flattened into branding, and where the aim is not influence, but understanding.

Until then, the knowledge economy will remain what it largely is: a marketplace of curated illusions, selling self-optimisation while displacing the very criticality that real knowledge demands.

Featured Image: The American revolutionary Benjamin Franklin visits a salon in 1780s Paris