A deep dive into Eighteenth Century fashion and society

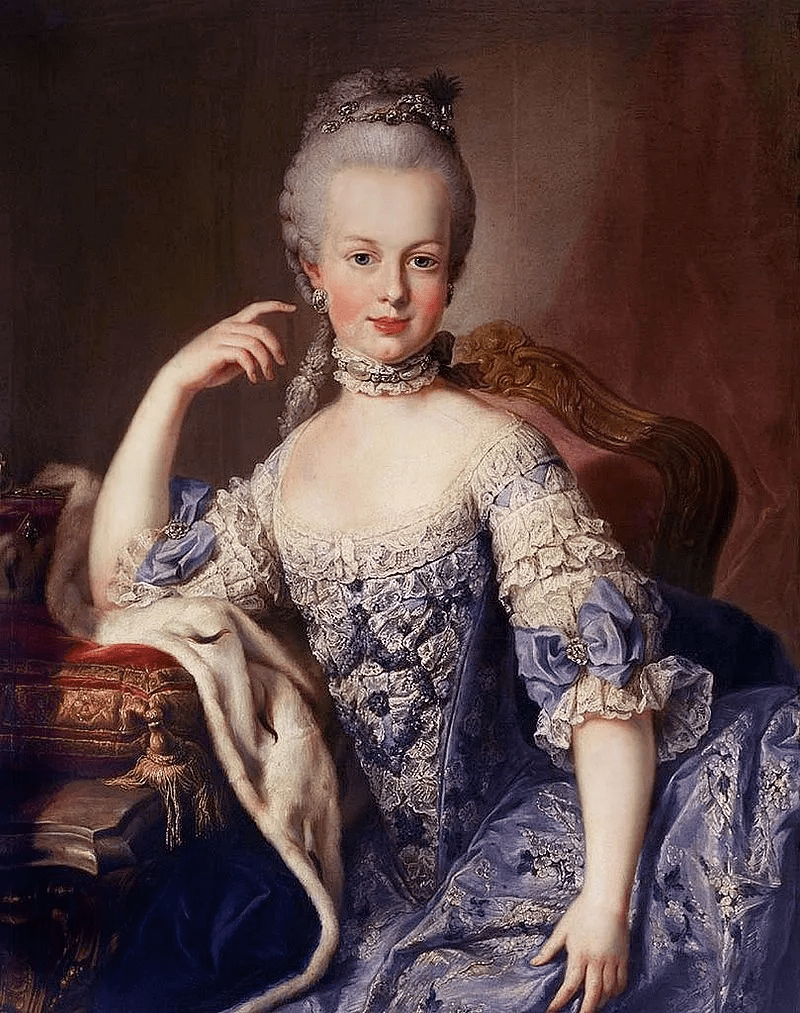

In the grand tapestry of fashion history, certain figures stand out, their influence echoing through centuries. One such icon is Marie Antoinette, Queen of France, whose life and style continue to captivate and inspire.

The Victoria & Albert Museum, a renowned institution for art, design, and performance, has announced a new exhibition celebrating Marie Antoinette’s unparalleled fashion legacy, and it’s an event that should undoubtedly be marked on your calendar.

As the V&A website eloquently states, Marie Antoinette is “a complex fashion icon, [whose] timeless appeal is defined by her style, youth and notoriety.”

This upcoming exhibit promises to delve into the “lasting influence of the most fashionable (and ill-fated) queen in history – with over 250 years of design, fashion, film and art.”

Sponsored by the esteemed Manolo Blahnik, the exhibition is set to open its doors on September 20th, 2025, offering a unique opportunity to explore the sartorial world of a queen who defied convention.

When studying fashion through the ages, it is indeed impossible not to feel the pervasive effects of Marie Antoinette.

As Queen of France from 1774 to 1792, her eccentric and often daring tastes reverberated across much of Europe. During a time when the French court rigidly adhered to strict rules and elaborate regulations, Antoinette boldly distinguished herself, becoming an embodiment of change and a catalyst for fashion evolution.

The eighteenth century in England witnessed a profound transformation in consumer culture, often referred to as the Consumer Revolution. At the heart of this societal shift was fashion, acting as both a significant driver and a key beneficiary of the burgeoning desire to consume. This era, marked by evolving social norms and economic structures, laid the groundwork for modern consumer economies, with the fashion industry playing a pivotal role. And nowhere was this dynamic more vividly exemplified than through the iconic, and often controversial, figure of Marie Antoinette, whose personal style and public image became inextricably linked with the era’s burgeoning consumerism.

Antoinette famously stepped away from the cumbersome conventional robes and gowns of her predecessors, prioritising comfort and freedom of movement. She is perhaps most commonly remembered for popularising the more relaxed and simpler robe à l’anglaise, a style notably inspired by English fashion, which championed a less restrictive silhouette.

So, was England worthy of influencing the Queen of France’s style?

Eighteenth-century English society, particularly in urban centres like London, Bath, and Birmingham, increasingly emphasised politeness and refinement. This cultural backdrop urged individuals to consume and outwardly display their wealth and status. Clothes became a fundamental means of adhering to societal norms and expressing self-worth, especially as people ascended social classes.

Marie Antoinette, with her lavish wardrobe and groundbreaking fashion choices, epitomised this societal emphasis on display. While her court was in France, her influence permeated European fashion, serving as a powerful, albeit extreme, example of how fashion could be used to assert identity and status. The Enlightenment further fueled this pursuit of refinement through education and empirical knowledge, fostering an understanding of manners and social etiquette that contributed to an air of civilisation and intellect, a concept Marie Antoinette’s refined (and sometimes unconventional) tastes undoubtedly challenged and redefined for the elite.

Marie Antoinette’s extravagant spending set a precedent. Individuals took immense pride in their attire, using clothing not just out of necessity but to flaunt their affluence and assert their identity.

Michael Kwass notes that the spike in clothing purchases is a clear indicator of the Consumer Revolution, and Marie Antoinette’s relentless pursuit of new trends and her substantial expenditures on clothing perfectly illustrate this driving force.

The accessibility of luxury goods and new trends across the social spectrum was crucial to the Consumer Revolution. The decline of sumptuary laws, which once restricted luxuries for lower classes and controlled imported goods, opened the door for wider consumption and blurred traditional class distinctions.

The burgeoning middle class was instrumental in disseminating luxury and fashion. Domestic servants, the largest female employment sector in the eighteenth century, played a vital role in transmitting the latest styles and spreading the desire for new commodities by observing and imitating their masters. While Marie Antoinette herself was at the pinnacle of society, the very extravagance of her fashion, particularly her more comfortable and ‘natural’ styles like those worn at the Petit Trianon, paradoxically made certain elements of her look aspirational and, eventually, adaptable for those with more modest means.

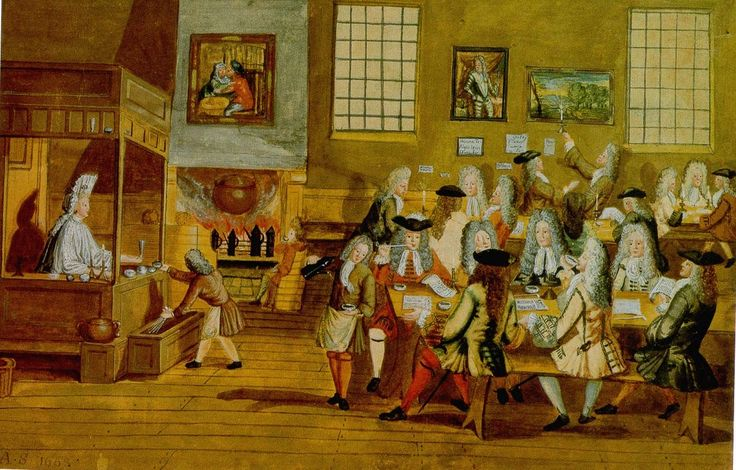

Urban infrastructure underwent significant changes that profoundly influenced consumer habits. London, in particular, boasted wide, smoothly paved streets with stone sidewalks, well-lit roadways, and richly stocked shops with glass doors showcasing an abundance of wares. This improved infrastructure transformed shopping into an enjoyable, social activity. The shift towards browsing as a pastime led to the increased importance of window-dressing and enticing shop displays, further driving consumerism. While not directly involved in London’s urban development, Marie Antoinette’s daily life at Versailles and her movements through the city of Paris provided the ultimate spectacle for fashionable observation and imitation. These venues not only gave people an excuse to acquire new luxuries but also propelled fashion’s influence and encouraged the consumption of exotic goods, with Marie Antoinette often leading the charge in adopting novelties. (Pinterest / European Coffee House)

Eighteenth-century fashion was a dynamic blend of styles, fabrics, and patterns influenced by global exploration and cultural movements. Exoticisms like Indienne and Chinoiserie heavily influenced clothing and home decor, and Marie Antoinette was known for incorporating such elements into her personal spaces and attire.

Marie Antoinette’s early reign was deeply intertwined with the Rococo aesthetic, particularly in her love for pastels, floral motifs, and delicate ornamentation. Cultural movements such as the Enlightenment and Romanticism also promoted rationality, natural motifs, and individualism in fashion, leading to her eventual embrace of simpler, more ‘natural’ styles that, despite their simplicity, carried significant political and social weight.

The establishment of knowledge networks through the passing of trends from country to country, notably from France to England, created a modern fashion system. It was precisely through this network that Marie Antoinette’s fashion choices, whether celebrated or condemned, were disseminated across Europe, making her a central figure in the nascent global fashion industry. The use of Pandora Dolls was a great step towards modernity, as the dissemination of styles was crucial to creating trends.

Fashion in eighteenth-century England was undeniably both a driver and a beneficiary of the Consumer Revolution, and Marie Antoinette’s influence served as a potent magnifying glass on this phenomenon, which is why you should go to the exhibit.