Step into Georgian London. There’s enlightenment and empire in a city humming with powdered wigs, candlelit stages, and something new in the air: consumption.

A shilling well laid out [graphic]: Tom and Jerry at the exhibition of pictures at the Royal Academy / drawn & engd. by I.R. & G. Cruikshank. Taken from Yale University Library Catalogue

The eighteenth century in Western Europe saw a consumer revolution for women who could afford it. There was a major shift in spending to shop rather than spending to survive, causing society to take an important step to modernity as we know it today. It wasn’t about just buying stuff; it was a whole new way of expressing identity, status, and desire through consumption, something we know well in a world of fast fashion and trends.

Middle-class and upper-middle-class women were the biggest drivers of this revolution, with disposable income and newfound time to spend in society, shopping and parading. Everything at this time was turned into a commodity. Including the women themselves.

Everything became about performance. Pavements widened for promenading down streets to window shop and show off your status to society. The line between fashion, fame, and sex blurred.

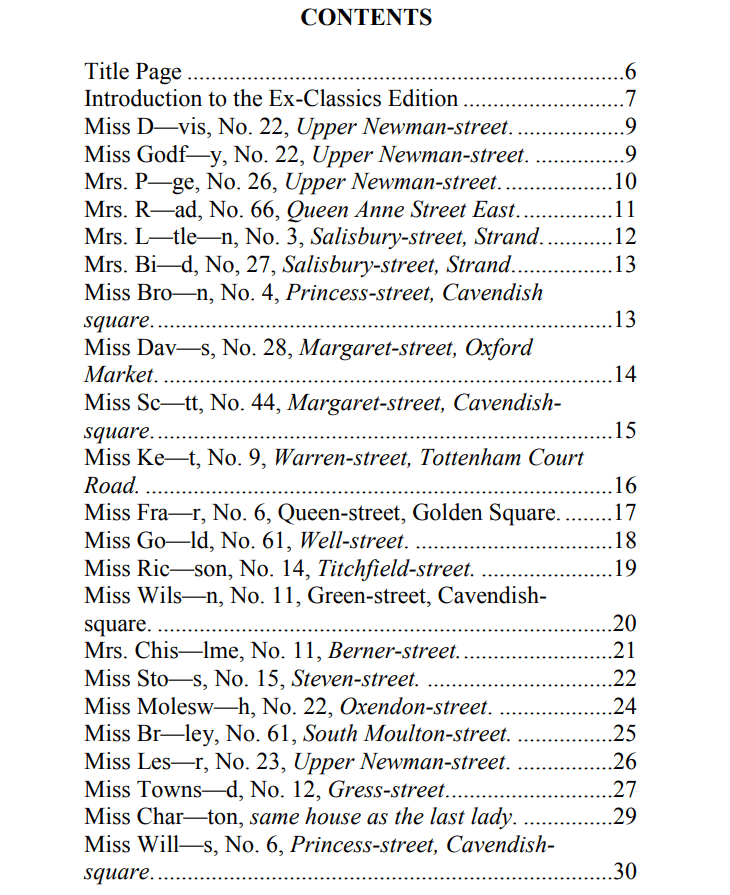

Those blurred lines were actualised in Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies. This was an annual directory running from 1757 to 1795, chronicling all of the prostitutes working in Georgian London. It turned women into consumable fantasies, and it existed and thrived because the culture was starting to see everything as consumable.

It was unofficially attributed to John Harris, a pimp and brothel keeper, and was the ‘little black book’ that all Georgian men carried around.

Comprehensive entries offered up each woman like a menu item, complete with descriptions of their looks, personality, their bedroom “talents”, price, and sometimes heart-wrenching origin stories with a tidy contents page. It detailed different women, their appearance, personality, and backstories. Some entries read like romantic prose, others like cruel caricature.

A woman with “a voice like silver bells” might be followed by one mocked for having “lost her teeth to the pox.” It was a bizarre mix of titillation and tabloid, glamour and grim reality.

These women weren’t just characters in a book; they were living contradictions, navigating a society that demanded virtue in public and vice in private.

Covent Garden was a theatre district and a red-light zone. The women in Harris’s List were at the intersection of performance and survival, both literally and figuratively, in the dark underbelly of exploitation in a theatre district cross-red-light zone.

It’s easy to be appalled. And we should be.

Some women gained financial independence and autonomy by owning property, choosing their clients, and helping other women get into the business.

However, the list and all it stood for were inherently deeply problematic. Many of the women were barely out of childhood and were coerced into sex work by poverty, abandonment, or desperation. The list was compiled, sold, and read by men for men. The power dynamics were never equal, even if it was one of the only ways women could earn their own money.

We can’t ignore the uncomfortable truth. Whether they were celebrated or scorned, used or helped, these women lived in a world that judged their worth by beauty, obedience, and availability, and Harris’s list is a record of that contradiction.

We can still feel the echo today. Just scroll Instagram or open a tabloid.

The stages have changed. The performance goes on.

Modern platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and OnlyFans turn ordinary women into highly visible, clickable personas. They must be “on brand,” beautiful but relatable, sexy but safe. Like the women of Harris’s List, they are appraised not just for who they are, but how they appear, what they offer, and how well they play the part. Today’s followers are yesterday’s paying readers. Aesthetic curation replaces the prose, but the purpose is the same: to perform desirability in a world that profits from it.

Reality TV is another modern-day List. Take Love Island or Too Hot to Handle. Women are introduced, assigned roles, “the sweetheart,” “the bombshell,” “the villain”, and then publicly evaluated by an audience hungry for both romance and drama. Even the emotional backstories echo Harris’s List’s flair for spectacle. “She was orphaned young and took to the streets” has simply become “she’s been cheated on before and just wants real love.” It’s commodification dressed up as reliability.

And then there are the celebrities. Female public figures are dissected with all the surgical precision of an 18th-century pamphlet. A woman gains weight? It’s news. Does she date too many people? She’s “lost her way.” She ages? She’s mocked. She gets plastic surgery to help with ageing? She should age gracefully. Just like the entries in Harris’s List, today’s commentary vacillates between admiration and cruelty, desire and derision.

Yet, just as in Georgian London, the story isn’t entirely one of victimhood.

Some women, then and now, have turned this visibility into power. Fanny Abington, once listed in Harris’s List, became one of the most celebrated actresses of her time. She transcended the role society handed her and used it as a launchpad. Today, influencers, sex workers, and celebrities alike are finding ways to control their own narratives, monetise their image on their terms, and sometimes even redefine what power and success look like. Fanny used her past to propel her career, not get trapped in that dark underbelly.

But we shouldn’t confuse agency with equality. Harris’s List was compiled by men, for men. So are many of the platforms’ women navigate today. The power dynamics haven’t disappeared; they’ve just gone digital. And while some women do gain independence, far more are exploited, coerced, or trapped in the same old performance: be beautiful, be available, be sellable.

Behind every powdered wig or flawless filter is a woman navigating that double bind, expected to be both product and performer, to seduce without seeming too sexual, to be visible without inviting danger.

So, what was Harris’s List, really? A catalogue of exploitation? A record of survival? A strange, early form of branding?

The answer is still: all of the above.

It documented the women who were the glittering faces of a society that both adored and destroyed them. It celebrated their appeal while ignoring their humanity. It offered some a path to wealth or fame, but it also reinforced a brutal hierarchy that judged a woman’s worth by beauty, obedience, and availability.

And that, perhaps, is the most enduring tragedy.

Because in many ways, the List never went away. It simply changed format. It’s in our explore pages, our reality shows, our paparazzi shots, our algorithms. The same gaze that once flicked through printed pages now scrolls through profiles. The same instinct to consume women, to sort them, rank them, desire them, discard them, is alive and well.

The performance may look different. But the audience hasn’t really changed.